My Contribution to “The Sprinter’s Compendium”

In August of 2016, Ryan Banta asked me to contribute to his book, “The Sprinter’s Compendium”. Ryan sent me ten questions to answer and I became one of the book’s 50 contributors. At 763 pages, The Sprinter’s Compendium might be the most comprehensive books on sprinting every published.

Ryan Banta gave me permission to publish my contribution to his book, and here it is.

1. Over your career what is the best concept, idea, training, you have adopted to use in training sprinters? Over your career what is the worst concept, idea, training, etc. you no longer use to training sprinters?

Best Concept = Max Speed

I have coached track since 1981. My epiphany came circa 1998-1999. MAX SPEED is the Holy Grail.

Nothing in the weight room translates to speed. The strongest athletes are not the fastest athletes.

I’ve had kids who could run 12 x 200, each in 27 seconds or better, who were not fast. Ability to run multiple intervals at sub-max speed does not translate to sprinting.

Kids who can run long distances are almost always poor sprinters.

Eighteen years ago I wanted to create a track program that would attract talented kids. Not only did I want to attract those kids, I wanted them to love their experience. I ran track in middle school, high school, and college but never looked forward to practice or meets. I wanted to create something different.

I attended a Medalist Track & Field Clinic in 1998. Paul Souza of Wheaton College (MA) was a dynamic speaker. Souza told the small audience that his 400 runners never ran more than 200 meters in practice. Four of them ran sub-48. Epiphany!

Speed development became the centerpiece of my program for the next 18 years. Along with high intensity speed drills, my kids were timed three times in the 40-yard dash at every winter workout. From the beginning, I would record, rank, and publish those times. In the early days, I would do my work on a spreadsheet and post the rankings on a bulletin board in the main hallway of our high school.

As technology changed, so did I. Starting in 2005, my rankings were posted on my track website. Soon those rankings migrated to Google Docs and now those links are posted on Twitter.

Record, rank, and publish evolved but so did other things.

In 2008, I heard Chris Korfist speak at a Chicago track clinic. Chris and I, at least training-wise, were like twins separated at birth. His max speed measurement was done with an optical system sold by Summit Timing. I had never heard of anyone timing the “10-Meter Fly”, but it made perfect sense. I bought the system a month later for $2000 and started timing 10-meter flys.

For the past nine years, I have been measuring 40-yard times and 10-meter times (simultaneously) three times per athlete, two or three times a week in the off-season. My 40’s are still hand-timed so I can compare my sprinters from the past 18 years. The 10-meter times are automated, of course, and I use Freelap now. I have the Freelap Pro Coach System with 21 FxChips.

The 40-yard dash forces athletes to accelerate (drive) and then get tall and sprint (max speed). The timing of the final 10 meters of that 40-yard dash forces athletes to reach max speed and finish by running though the finish line.

Improving max speed improves a sprinter. How can this be disputed?

Max speed always correlates to sprinting. Despite this undeniable truth, coaches still hammer their sprinters in the weight room, demand arbitrary numbers of sub-max intervals, and sometimes prescribe long slow aerobic work.

Worst Concept = Sub-Max Speed

The opposite of the best concept is the worst concept. Poetic huh?

I am 18 years removed from 30-minute runs, timed miles, “Indian Runs”, and all other types of aerobic training for sprinters.

My sprinters never run “ladders” or “tempo runs”.

My sprinters do approximately 25 “lactate workouts” during our competitive season. February, March, April, and May are the only months where we do lactate workouts. Meets are lactate workouts. With 18 scheduled meets, we are left with approximately seven lactate workouts done in practice.

The total sprint distance in a lactate workout is between 400 and 800 meters, usually 400 to 600. The longest we ever sprint in practice is 200 meters at a given time.

Lactate workouts are the only time we run sub-max. And when I say sub-max, everyone observing would describe it as sprinting. The slowest we ever run is goal-400 pace. If we have a 50-second 400-runner, that guy is never running 26-second 200s in practice. Never.

I probably should add, we never run against the wind, we never push or pull a sled, and we damn sure never run with a parachute on our back.

Speed is neurological. Getting strong, fit, or in-shape has little to do with speed. In matter of fact, getting strong, fit, or in-shape can be counterproductive to getting faster.

“In speed development, the nervous system only understands quality.” – Boo Schexnayder

2. What periodization model do you feel best fits your method of planning an athlete or group’s training and why? Do you use different models at certain points in the season? To subscribe to a long to short, short to long or concurrent method?

I am a high school coach and believe in the multi-sport concept. What does that mean in today’s world? Well, that means football and track should merge off-season training programs. Forget about the specialists of the world. Track coaches seldom, if ever, get a kid who plays soccer, lacrosse, or basketball. Baseball players never run track. The only kids I get are football players and kids that can’t shoot and can’t hit.

My periodization is pretty simple:

a) Summer – Football Workouts

b) Fall – Football

c) Winter – Max Speed

d) Spring – Track Season

If I was coaching non-football players, this would be my plan:

a) Summer – Max Speed

b) Fall – Max Speed

c) Winter – Max Speed

d) Spring – Track Meets, Lactate Workouts, and lots of Rest & Recovery

I’m obviously a short to long guy. Can’t get much shorter than 10-meter flys and 40-yard dashes.

We get fast all year and then we train to hold our speed for up to 400 meters. The opposite approach sounds ridiculous to me. The idea that all philosophies are equally correct is hogwash.

We build a sprint base in off-season.

I’ve used these quotes when doing presentations; I believe I am the originator of all five.

a) 6-6-6 … Training pays off in six weeks, six months, or six years. What we do today does not change us tomorrow.

b) Run fast to get fast, you don’t plant beans to grow corn.

c) Speed grows like a tree and speed only grows when you sprint.

d) Sprint as fast as possible as often as possible staying as fresh as possible.

e) When you record, rank, and publish, sprinters never forget their spikes.

3. Please give us a sample micro-cycle (7-14 days) of training from the beginning of the season, the middle of the season, and during your championship meets.

Sprint Specific Micro-Cycles

February (Pre-Season, Indoor Season)

Monday – speed drills and timed sprints of less than 5 seconds (flys, block starts, etc)

Tuesday – speed drills and x-factor (non-sprinting strength, explosion, and neurological training)

Wednesday – speed drills and timed sprints of less than 5 seconds

Thursday – speed drills and lactate workout (something like full speed 200, 8 min recovery, full speed 200)

Friday – no practice

Saturday – no practice

Sunday – no practice

Monday – speed drills and lactate workout

Tuesday – speed drills and x-factor

Wednesday – speed drills and timed sprints

Thursday – speed drills and fundamental work (hand-offs, block starts)

Friday – no practice

Saturday – indoor meet

Sunday – no practice

April (Competition Season)

Monday – full-team triangular meet (counts as lactate workout)

Tuesday – sprinter holiday, no practice

Wednesday – speed drills, x-factor

Thursday – speed drills, timed sprints

Friday – speed drills and fundamental work (hand-offs, block starts)

Saturday – Invitational

Sunday – no practice

Monday – full-team triangular meet

Tuesday – sprinter holiday, no practice

Wednesday – speed drills, x-factor

Thursday – speed drills, fundamental work

Friday – Invitational

Saturday – no practice

Sunday – no practice

May (Championship Season)

Monday – speed drills, lactate workout

Tuesday – speed drills, x-factor

Wednesday – speed drills, fundamental work

Thursday – Conference Meet

Friday – no practice

Saturday – no practice

Sunday – no practice

Monday – lactate workout

Tuesday – speed drills, x-factor

Wednesday – speed drills, fundamental work

Thursday – Sectional Meet

Friday – no practice

Saturday – no practice

Sunday – no practice

Notes:

a) We never do lactate work more than once or twice a week

b) In every cycle there is a minimum of four days off per 14-day cycle. In the Championship Season, we take six days off per 14-day cycle.

c) Health always trumps a workout.

d) The holy trinity of sprinting: rest, recovery, and growth

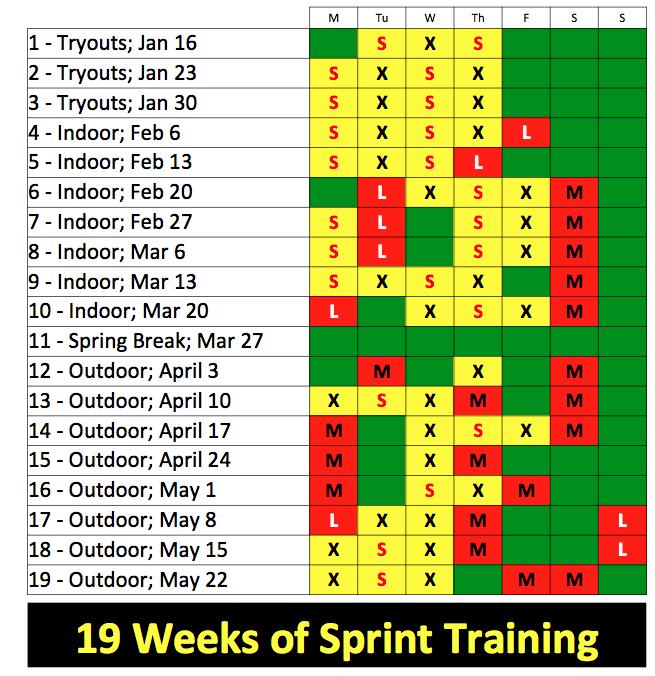

The grid below shows sprint days (S), x-factor days (X), lactate workouts (L), and meets (M). Yellow days are alactic, red are glycolytic (lactate), and green are rest and recovery days.

4. What tapering strategies do you use to bring your speed athletes to a peak cycle?

We take three days off every week during our Championship Season. I’m not talking “easy days” here, I’m talking “go home after school and take a nap”.

Our volume is very low in December and January; everything is alactic (maximum intensity for 5-10 seconds). Volume is increased in February, again in March, and peaking in April. May resembles February.

6. How has your strength training evolved over your coaching career? What have you adopted when it comes to your strength training over the years and what have you removed? Why did you make these changes?

When I first started in the weight room, I used an adaptation of Bigger, Faster, Stronger. I liked the record, rank, publish part of BFS. To this day, BFS is probably better than most high school weight programs.

“Indifferent and Confused” sums up my present opinion of the weight room strength training to improve speed.

I believe lifting weights to improve speed is analogous to America’s foreign policy, perpetual war to promote peace, love, and understanding. How did the weight room ever become a centerpiece for sprint training?

Sprinting is the best strength-builder in the world. My football-playing sprinters spend lots of time in the weight room. My non-football-playing sprinters seldom lift. All of my sprinters look like wide receivers and running backs. Sprinting, in and by itself, improves strength.

Weight lifting increases the size and strength of slow-twitch red muscle fibers. Sprinting and jumping are the result of fast-twitch white muscle fibers. The strongest guy in the weight room is seldom, if ever, the fastest guy in the 10-meter fly. Weight rooms seem to be populated by slow guys who want to get big.

Not only is weight lifting generally a poor predictor of speed, there is no specific lift in the weight room that is specific to sprint excellence. Everyone seems to agree that power cleans improve speed. Once again, I disagree. Power clean all-stars are seldom sprinters. Sprinters are good at sprinting and jumping.

This guy is good at power cleans. No way does this guy make my 4×1 team.

This guy is good at speed bounds. When I see this, I see speed.

Strength is good. How can anyone argue? However, until someone shows me something in the weight room that has a direct correlation to speed, I will see the weight room as a mixed bag of mostly bad ideas perpetuated by speed-challenged body builders.

Body building in the absence of speed training will always result in slower speed times.

These are the only three things guaranteed to improve sprinting: sprint mechanics, max-velocity sprinting, and jumping.

6. How do you handle recovery in your daily, weekly, and annual planning? How do you manage recovery in between intervals?

I run a data-driven sprint program. How much rest does a sprinter need? Simple. The sprinter needs enough rest to run max-speed. We never sprint injured, beaten-down, or too-tired-to-run-fast.

We never sprint the day after a lactate workout or a competition.

If I have a sprinter who runs a fast 1.00 in the 10-meter fly on an average day, I don’t allow sprinting at 1.08. Sub-max sprinting reinforces sub-max sprint mechanics. Taking the day off is always better than running a slow, sloppy, half-assed sprint workout.

Every year, my sprinters take a spring break vacation. Our spring break separates our indoor and outdoor season. I go to Fort Lauderdale for five days (sprint coaches need rest, just like their sprinters). One thing I can guarantee, the first meet after spring break, we will be faster than lightning in the 100, 200, 400, and the sprint relays. Rebooting the nervous system and allowing the body to rest, recover, and grow provides magical results.

By the way, the 4×400 is a sprint relay. Anyone who tells you otherwise is probably a distance coach and doesn’t understand sprinting.

7. How do you handle the volume in your personal workouts (Day to Day, Week to Week, and types of workouts)? How do you ensure that proper rest is given in a particular workout to obtain the level of rest you are attempting to achieve? Is it based on time alone or do you use heart rate monitors or other devices to help provide data to produce the maximum effect?

Speed data provides the feedback I need. I also communicate with my sprinters. Every sprinter in my program understands my philosophy. We improve by running fast but if we can’t run fast, taking the day off is the next best option.

Who needs heart rate monitors when you have access to direct measurements like the 10-meter fly?

We never talk about how many minutes of rest kids need between timed sprints. They know.

8. What do you think is unique about your program you do to build culture?

Let’s start with happy and healthy. When my kids look forward to practice, practice is good. When my kids look forward to meets, they compete well. This is a total departure from my experience as a track athlete from 1972 through 1980. I once said, “The only thing good about track practice is when it’s over.” I had panic attacks thinking about upcoming meets. I grew up in a militaristic “let’s get tough” track culture. At Plainfield North, our culture is all about speed and winning races.

My sprinters own their team. I work together with my sprinters to make our sprint program the best it can be. I trust my athletes and they trust me.

In addition to the happy and healthy mantra, my track team wears cool uniforms and we have the best schedule in Illinois. We travel (two over-night trips) and generally run in the best meets possible.

Plainfield North is promoted more through Twitter (@pntrack) and photography than any team I know. Our pntrack.com website is extensive.

9. How do you evaluate an athlete when they first enter your program? How do you evaluate during long prep cycles? What type of testing do you do in the preseason, mid-season, or championship phase? I.E. Workout Load/Event Group

I time 10,000 sprints every year. Max speed is the key to track speed. No other predictor comes close. I teach to the test by running fast. Speed grows like a tree and I want my kids to grow every day.

We run fast to get fast, but I’m also able to evaluate my sprinters each and every workout. This year (2016), my fastest four 10-meter fly guys in winter workouts (over 130 on the roster) ended up running on my 4×1 team. Each guy averaged 1.02 in the 10-meter fly. They ran 41.72 in the 4×1, ranked #4 IL.

I had a coach ask me, “Can you tell who will run on your 4×1 based on 10-meter fly times?” I would consider the question rhetorical. Never will a 1.08 sprinter outperform a 0.98 sprinter if both are healthy. Usain Bolt ran the fastest 10-meter segment in human history, 0.81. Enough said.

10. What strategies do you employ when planning an athlete’s training in multiple (sometimes very different) events and still get the necessary speed training? What environmental, cultural, and schedule issues affect your planning? How do you handle planning for and/or around those events?

We hurdle train in spikes twice a week, never going over more than two hurdles in the highs or two hurdles in the intermediates. This includes meets. If we have two meets, we have no hurdle practice that week. If we have only one meet, we have one hurdle workout. We do non-impact hurdles drills daily.

Like our hurdlers, our jumpers jump twice per week, including meets. If we have only one meet, long jumpers will practice once, triple jumpers once, and high jumpers once.

Throwers and vaulters practice their specialty every day.

Our distance group practices separately. Distance training is very different than sprint training.

Weather influences my practice plan in a big way. I want good weather for our most important workouts (lactate workouts). Technical work like handoffs, block starts, and hurdles are practiced in good weather. No skillwork is better than bad skillwork.

If an athlete has a conflict and can’t attend practice, they are expected to communicate that absence to their coach. Our official season in Illinois is 20 weeks in length (January 18 to May 28). Coaches need to be both demanding and flexible. If the correct culture exists, attendance never becomes a problem.

+++

Tony Holler has taught Chemistry and coached track for 36 years at three different high schools, Harrisburg (IL), Franklin (TN), and Plainfield North (IL). Inducted into the ITCCCA Hall of Fame in 2015, Holler’s teams have continued to feature great sprinters. Along with Chris Korfist, Holler co-directs the Track Football Consortium held twice a year (June and December). Holler has written over 100 articles promoting the sport of track and field and sharing everything he knows. His articles can be found at ITCCCA.com, FreelapUSA.com, and SimpliFaster.com. You can follow Coach Holler on Twitter @pntrack and email him at tony.holler@yahoo.com.

Don’t miss videos from past consortiums! Videos