“Speed training is really pretty simple. Why is there so much confusion?” -Tony Holler

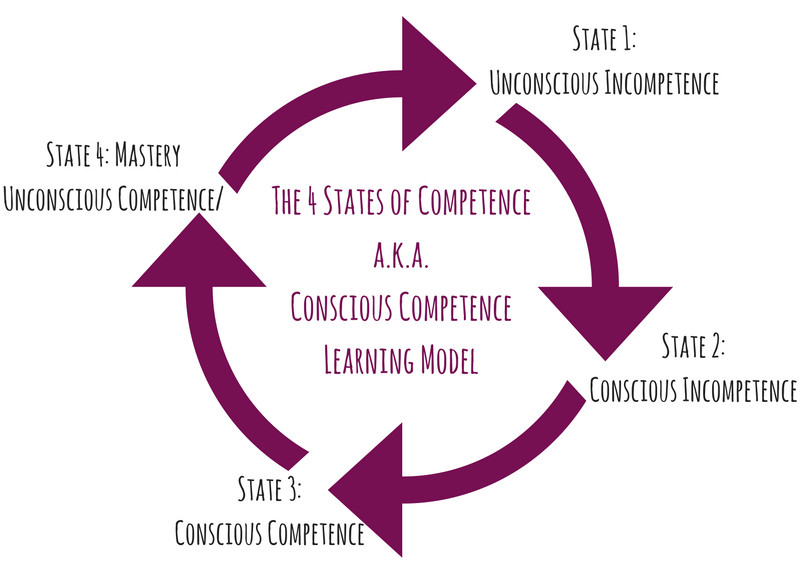

Assise: When I first read this, I had at least 15 reasons run through my head. After lots of thought, I boiled it down to two things: unconscious incompetence and ignoring specificity. After further examination, I think unconscious incompetence takes care of it.

Let’s start with what may be the worst case scenario, conscious incompetence. This would mean coaches see value in speed training but choose not to do it. Sounds foolish, but I bet it happens. Coaches are afraid to divert from the norm. Dogma is powerful.

Holler Comment: At the college level, the fear of a hamstring injury is real. The weight room is so much safer. College S&C coaches are sometimes one injury away from getting fired. High school coaches copy college programs.

Assise Response: I have been guilty of this in the past. It seems so illogical to me now to copy and paste programming. No two situations are identical. However, novice coaches who are creating their own programming may be better off copy and pasting a quality program. As a young coach I thought I had numerous original ideas. Most turned out to be unoriginal, ineffective, or stupid. An essential-rich template would have been helpful. I should make note that I am all for creativity, but a mistake many make early on is trying to be creative too often.

Holler Comment: I would advise young coaches to visit coaches who are good at what they do. Watching a coach do work is ten times better than a clinic presentation. Get creative once you have a strong foundation. In addition, stop idolizing college coaches. The best college coaches recruit a stable of first-round draft picks. It’s a rigged game at the college level.

Assise Transition: Unconscious incompetence = coaches totally unaware that attaining maximum velocity is the best way to improve speed. They do not know that something like 3 x 40 meters (timed) with 5 minutes rest between reps is a safe and extremely effective protocol for high school athletes.

Holler Question: How would you try to convince someone that 3 x 40 meters is safe?

Assise Response: If a person feels sprint training is not safe, I would make the assumption it is because they see injuries occur when athletes are sprinting in competition. I think trying to convince them that the activity itself is safe would be counterproductive because injuries can happen during any activity. If I were to sell it as safe, and an athlete was injured, it would be my fault and the coach would scrap the idea of sprinting.

Instead, my approach be this: if you don’t train maximum velocity, you are not preparing your athletes for competition. Cameron Josse summarizes this well,

“The butterfly effect of training speed trickles over into maintaining health as well. When looking at the physics, there is virtually no exercise outside of sprinting that exposes an athlete to the same combination of power, speed, elastic recoil, rhythm, coordination, and more. There’s a reason that sprinting is often referred to as the most intense activity the human body can produce. If athletes understand the basics of sprinting safely and efficiently, they can prime their bodies to build resiliency.” – Cameron Josse

Coaches who are in sports where athletes do not reach maximum velocity (basketball, volleyball, badminton, etc.) may argue that there is not a need to train at maximum velocity because it is not a component of their game. Besides building a more robust athlete and challenging an athlete’s nervous system to the highest degree possible, sprinting has also been shown to improve acceleration, strength, change of direction, and speed reserve. Furthermore, I’ve heard a guy say, “We train at 100 mph so 80 mph seems easy.”

For those truly hung up on sprinting being a risk, I would encourage them to begin with shorter sprints. A possibility could be 6 x 20 m completed 2 – 3 times in a week. Then, 5 m could be added onto the reps each week, while keeping total volume under 150 m.

I should make note, 150 meters is a guideline. I think there are benefits with AREG principles for athletes who can continue to hit times within ~5% of their PR. That being said, I do think keeping the volume low allows for achieving sizable gains with minimum risk.

Holler Comment: In addition, low volume maximizes the next day. What have you gained if today ruins tomorrow?

Assise Transition: I wonder why people are unaware that attaining maximum velocity is the best way to improve speed, and I think the biggest culprit is lack of curiosity. People will stay within their comfort zone. For many, this means grindy workouts on the field/court or in the weight room.

For some reason, lack of curiosity amongst coaches is common at the high school level. Most coaches achieve enough success to justify whatever they are doing. Don’t get me wrong, I love progress. A big part of why we measure athlete performance (in practice and competition) is to motivate. Progress fuels motivation. We know chemically when a personal best is attained, there is a big dopamine hit, and that is what keeps the athlete striving to improve.

Holler Comment/Question: Job security is a culprit, too. Do you think people are afraid of record-rank-publish because, in their mind, speed is genetic?

Assise Response: I definitely see that as a contributing factor and I think we would both agree that part of sprint ability stems from an athlete’s parents. However, we both also know that speed is a characteristic that can be developed much more than most people think. Many dismiss it and never give it a chance to blossom.

Holler Question: Could another reason to avoid record-rank-publish be the vulnerability which comes with it?

Assise Response: Yes. But the beauty of R-R-P is it fosters competition, maximizes intent, and celebrates progress. If the athletes ran slow times in the 10 meter fly, there would still be value in the system. The desire to improve would still exist.

Holler Comment: Also, there’s no doubt in my mind, the average coach was a slow, overachiever. We are defined by our past.

Here’s a third issue. High school coaches try to turn boys into men. They want that 140-pound freshman to be a 190-pound senior. How? The weight room, of course. When this happens they give credit to the weight room. We have no way of separating natural growth from weight room growth. I truly believe that size is the #1 priority of most high school football coaches. Then they complain about speed.

Assise Comment: I think “Bigger, Faster, Stronger” philosophy to most coaches really means get as Big and Strong as possible… as Fast possible. Unfortunately speed fails to come along for the ride!

Assise Transition: All this being said, the target should not be progress, the target should be optimization.

The beauty of optimization as the target is we have no way of knowing if it has been attained. It is like chasing a unicorn. If we are chasing after an unknown, curiosity is our best method to get close to it. Curiosity also opens up different avenues and risks that can be taken in order to meet the desired objectives.

Many coaches lack the courage to do this. Coaches will stick with what is safe. “Progress” will suffice. If coaches see improvement, they think, “why change?”

Holler Comment: The courage thing is interesting. What are they afraid of? I think they fear the minimal dose training, staying fresh, and making rest a priority. I think they fear being labeled soft and lazy. “The Grind” is so much safer for them. I wish I had a dollar for every coach I’ve heard call a fast kid lazy.

Assise Response: “The Grind” is their defense. If they lose, they can fall back on “outworking” everybody. Our society is so hung up on doing things just to be able to say they did things. It doesn’t even matter if there is a positive outcome. Personally, I would rather have 3 ounces of Kobe beef than 300 pounds of ground chuck.

The love affair many coaches have with the weight room is the perfect example. Yes, high school athletes get stronger when they lift weights. Yes, most high school athletes get faster when they lift weights. So, most coaches are satisfied with those outcomes.

You know what else gets many male high school athletes stronger and faster?

Continuing to breathe. Puberty and general growth are pretty freaking powerful.

What’s the best way to get faster? True sprinting! If someone told me they had two months to learn how to swim, would it make sense to suggest bike rides? Of course not. A better approach would be to get in the damn water. Yet this is the approach many take. Instead of sprinting to get faster, they will do everything but sprinting in an attempt to get faster.

Holler Comment/Question: Planting beans to grow corn. But what if you owned a bike business?

Assise Comment: Great question. One of the most important pieces of advice that I can give to athletes and parents is to be aware of those who do not have the best interests of the athlete at heart. This is multi-faceted:

◊ Event organizers who are looking for anyone with a heartbeat to attend their events. Parents and athletes need to understand there’s a business side to events like 7-on-7 tournaments and AAU showcases. Exposure to college coaches are promised for all who pay to be a part of the event. What the event organizers do not tell you is they do not charge everyone to attend. They will waive the entry fee for the athletes who attract the college coaches (if the college coaches even deem attending the event worthwhile). If you are paying, you probably are not on anyone’s radar, and it is questionable if having a great performance at the event will put you on anyone’s radar.

◊ Club coaches who are looking for clients to fill their pocket. I am DEFINITELY not saying all club coaches are evil. There are terrific people involved in the club coaching scene and I think the vast majority have great intentions. However, parents and athletes should be aware there are people who make empty promises about an athlete earning a college scholarship and overcharge for their services along the way.

◊ The private trainer who is looking for clients to fill his/her pocket. Just like the club coaching scene, there are great people in the private training sector, but there certainly some who have monetary intentions which are not pure.

Even when intentions are pure, the one constant that has existed in my experience with athletes who have a private trainers is it makes things more complicated. In order to deal with the complexity, all parties involved have to be transparent. I have had numerous athletes return from a day of rest completely fried from a session with their private trainer. Not ideal. I have also had athletes who were identified as needing work in a specific area, and the private trainer has had an opposing viewpoint and has the athlete do work which contradicts what is done at the school practice. It is irrelevant if the school coach or the private trainer is more correct regarding the athlete’s needs. The issue is it puts the athlete in a position which is complicated and is far from optimal.

Holler Comment: I’ve witnessed private trainers intentionally and unequivocally trashing a kid’s high school program in order to promote his own (and improve his income). Parasites!

How can this be avoided? Parents should ask private trainers if they are willing to communicate with the school coach to set up a plan that works best for the athlete. This is complicated, but it can be done if the parties involved are reasonable. Keeping the focus on the best interests of the athlete is paramount.

◊ The school coach, club coach, or private trainer whose training methods are faulty. Parents and athletes should not be mesmerized by gadgets and gizmos promising to elicit magical results. The same goes for mystical workout plans which have produced numerous elite athletes. Whether a service is being paid for outside of the school, or their son or daughter is part of a program within the school, parents have every right to ask the following:

- What are the essential components of their physical preparation program?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of their son/daughter?

- How will the program be adapted to the athlete to improve the weaknesses and enhance the strengths?

- What have been their primary influences in training design and what do they do to continue their professional development in physical preparation/coaching?

◊ The school coach who uses the athlete to serve the coach’s interest. The primary example of this is the school coach who discourages multi-sport participation. Before an athlete athlete goes along with this type of coach’s advice, he or she should ask whose interest he/she is serving.

Assise Transition: You want to have your cake and eat it too in regards to speed and strength?

Build everything around speed and everything else falls into place. This doesn’t mean you can’t lift weights. Just don’t let it get in the way of enhancing speed. Slow cook size and strength while providing maximum exposure to time spent at maximum velocity, done through a minimum dose.

Holler Comment: The muddy water becomes crystal clear.

Assise Transition: How does this apply to a track coach invested in speed improvement?

As I read through this, I think about how I would classify myself. Conscious competence would seem to be a fair assessment. I am aware of how to implement and execute a speed training program. Over the years, athletes have produced results which would indicate competence. However, just by picking up a book, reading an article, listening to a podcast, or having a conversation with a peer can instantly put me in a state where I feel incompetent in comparison to the author or peer (and that is just fine). For me, these resources continually put me in a state where I am motivated to become better.

Holler Comment: “Certainty is the enemy of growth. Uncertainty is the root of all progress and all growth.” – Mark Manson, “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck”

Assise Closing: I recently had a conversation with a friend about the difference between knowledge and understanding. He summed it up nicely, “Knowledge is cheap, understanding is what people pay for.” As I am in my quest to become as competent as possible, I am aware competence is rooted in the desire to develop understanding. Understanding involves investigating below the surface. Anyone can implement a speed training program, but understanding how those who are in it can be best served by it is a much more complicated endeavor. True understanding of speed training requires a marathoner’s lens.

Rob Assise

@HFJumps

robertassise@gmail.com

Speed training is not at all an easy task to be honest. It requires 100% dedication in order to achieve results from the training. I don’t understand how some people think that it is a piece of cake.