The Origin, Evolution, and Future of Record-Rank-Publish

Alternate Title: When BFS Met FTC

Back in the 1960’s people read newspapers. My dad taught me to read box scores and understand statistics. I was fascinated with the leaders in statistical catagories. I have no idea why I was so drawn to statistics and rankings.

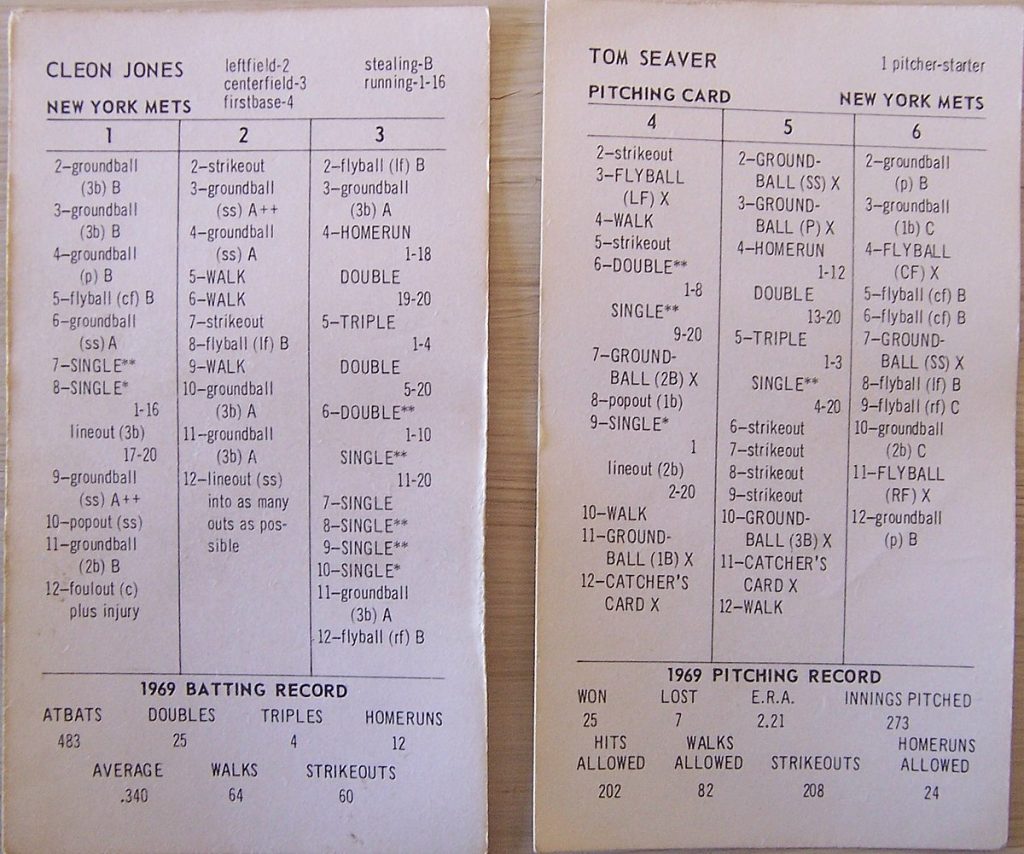

In 1970 I scraped together all the money I had and bought a game called Strat-O-Matic Baseball. I could only afford to buy six teams (major league teams from 1969). Strat-O-Matic was a game played with three dice. The white die determined whether to look at the hitters card (1,2,3) or the pitchers card (4,5,6). The red dice told you where to look in the columns 1-6 to find the result of the at-bat. Because the game was based on actual statistics from the year before, outcomes were very realistic.

These cards bring back memories. I bought six teams in 1970 including the 1969 Mets..

I played hundreds of games and kept scorecards for all of them. I compiled stats. I ranked player’s batting averages, earned run averages, homeruns, and RBIs. If I would have had Google Sheets and a Twitter account back in 1970, I would have posted those rankings. I think my dad worried that I was playing too much Strat-O-Matic and not enough baseball.

Stats and rankings never left me. In grade school, my dad’s basketball players called me “Pencil-Head” because I carried a clip board at basketball games and kept stats. Looking back, I might have been a little weird.

I was way too aware of my own stats as an athlete. I can remember scoring ten first quarter points in a 5th grade basketball game and extrapolating my point total to 40. In baseball, I recalculated my batting average in my head after every at-bat. As a high school quarterback, I was ultra-aware of my passing percentage, yards per completion, etc. I remember my track times to this day. Ok, I was definitely weird.

I was stat-obsessed as a head basketball coach in the 1980’s. I kept per-32-minute stats for all my players. I kept points per possession stats. I used ratios like assists per turnover and points per shot attempt. By 1988, I was entering my basketball stats on an Apple IIe and saving them on a 5.25 inch floppy disk.

I often tell my students that I see the world in numbers. It’s no accident that my teaching career is ending with me teaching chemistry and coaching track. Chemistry is the most quantified science. Track is the most quantified sport.

You get the point. I was destined to be where I am today. Record-Rank-Publish pre-dates the dawn of Feed the Cats (1998).

Winter Work Group 1996-2004

I finally divorced basketball (or basketball divorced me) back in 1996 (an ugly divorce). With my winters free, I took charge of the winter training program at Harrisburg High School. Harrisburg athletes did not take “PE”, they took “Athletics”. Freshmen had 1st period Athletics, everyone else had 7th period Athletics. This was the brainchild of Harrisburg’s Athletic Director, Gene Haile (the high school coach of Jerry Sloan). Athletes were athletes for the entire school year. In essence, athletes in season started practice an hour early. Teachers bitched about coaches “double dipping” but it was great for kids. In addition, it created one of the best small-school sports juggernauts in the history of Illinois. Harrisburg teachers taught six classes, coaches taught five classes and one class of “Athletics”. The football coach had two periods of Athletics (1st and 7th). Maybe that’s why Harrisburg qualified for the football playoffs 17 times in my 23 years there (1981-2004).

Not only did athletes start practice during the last period of the school day, athletes not in a sport had a mandatory 7th period workout. Athletics served as the PE class for athletes. Makes sense. (Band is a part of the school day, why not athletics?) Instead of playing dodgeball, square dancing, or walking laps, Harrisburg athletes did athletic training. In any given season, Harrisburg’s best athletes played a sport. Harrisburg set the standard for multiple sport athletes (see the Patton Segraves story, Born to Compete). Starting in 1996, I was in charge of 7th period “work group” in the fall and winter. In the fall, we ran two or three miles every day. The football coach (Al Way) wanted anyone not playing football to be punished by running, so that’s what we did. Seems archaic and mean-spirited to me now, but that’s the way it was. We really believed every athlete should play football or run cross country. Our fall work group was usually less than 25 kids. The math is pretty crazy. We had less than 300 boys in the school and sometimes 200 were in Athletics. Our football numbers sometimes approached 180.

Winter “work group” was different. With far less participation in wrestling and basketball, our “work group” numbers were bigger. We divided the group into two, creating a manageable high-intensity group of around 4o athletes, and a “lets have fun” group with the kids that weren’t any good. We referred to that group as the Kamikazes and they played games. Once again, seems archaic and mean-spirited to me now, but that’s what we did and it produced exceptional results. Harrisburg’s success in football, basketball, baseball, and track was unmatched.

So what do you do with a group of 40 decent athletes during the winter? The conventional wisdom was lift weights and run. For the first couple years, I basically supervised the weight room on Monday-Wednesday-Friday and we did a workout on Tuesday and Thursday. Workouts were basically “lets work real hard and get real tired”. In 1998, I transitioned to “Feed the Cats.” In 1999, I read the book “Bigger, Faster, Stronger”. BFS was a data-driven program that encouraged athletes to break records every day. You can’t break records if you don’t record numbers. As a disclaimer, I don’t necessary endorse “chasing numbers” in the weight room, but from 1999 to 2004 we did, and the results were outstanding.

Bigger, Faster, Stronger had core lifts that were done every week. The sets and reps changed every week for four weeks, then the cycle started over again. I loved the idea that in the fifth week (repeating week one), athletes would be breaking their own records. In week six, they would be breaking their records from week two. Being a track coach and understanding the power of the “PR”, I immediately saw the value of BFS.

I didn’t like the complicated BFS Record Cards that, of course, you had to buy. I also didn’t like every athlete filling out his own card. I simplified the process and adapted BFS to our situation.

I came up with six core lifts. Some of them are core lifts only because they are easy to measure (and thus the problem with chasing numbers). (*** On a side note, measuring things because they are easy to measure infects education like a cancer. Anyone who thinks a multiple choice test can measure the value or effectiveness of my chemistry class is a idiot. Don’t get me started.)

Our six core lifts:

Bench Press

Hex-Bar Deadlift

Parallel Squat

Power Clean (from the floor)

Pull Ups

Dips

I know, those of you who are weight-room-sophisticated are shaking your head right now, but hear me out.

We lifted on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. We sprinted on Tuesday and Thursday (*** Remember, beginning in 1998, I started using the term “Feed the Cats” and we stopped running and started sprinting. I also started my evolution towards rejecting grit, the grind, and no-pain no-gain.)

We had only a handful of squat racks and a handful of benches. We didn’t have much else. I talked the A.D. into buying a couple hex bars. We bought a couple sets of colored bumper plates for olympic lifts. We bought a glute-ham machine from BFS. I built plyo boxes so we could do the BFS “bench squat”. I put BFS posters on the walls to aid in the teaching of lifts never before done in Harrisburg, IL.

With our new equipment, we still didn’t have the resources to have all 30-40 guys do the same lifts on the same day. I worked out a rotation where one-third of the group (the lightweights) did “Squat Day”, the middleweights did the “Clean Day”, the heavyweights did the “Bench Day”. The next session, the assigned lifts would change. Only 13 guys squatted on a given day. Only 13 guys did power cleans on a given day. This is how we survived with limited resources.

Squat Day: parallel squat (recorded), pullups (recorded), and two assigned auxiliary lifts

Clean Day: power cleans (recorded), dips (recorded), and two assigned auxiliary lifts

Bench Day: bench (recorded), dead lift (recorded), and two assigned auxiliary lifts

I chose to make it simple. I always choose to make it simple. Athletes had two core lifts and two auxiliary lifts to do on a given day. I would vary the auxiliary lifts (including things like RDLs, incline bench, box squat, lunges, split squats, bent rows, etc.) I had a manager or an injured athlete hold the clipboard and athletes simply reported their numbers. We only recorded the maximum weight lifted a minimum of five reps. In order to encourage perfect form, we did five reps of everything. With dips and pull-ups we recorded the sum of three sets (unlimited rest). For pullups, our rule was the head had to come under the bar. For dips, the arm angle had to go to 90 degrees. At the end of the day, my clipboard had 80 numbers recorded, two for each kid. Most guys continued to do other lifting beyond the required four. When your require only the minimum, athletes tend to give you the maximum. #BuildYourOwnHouse

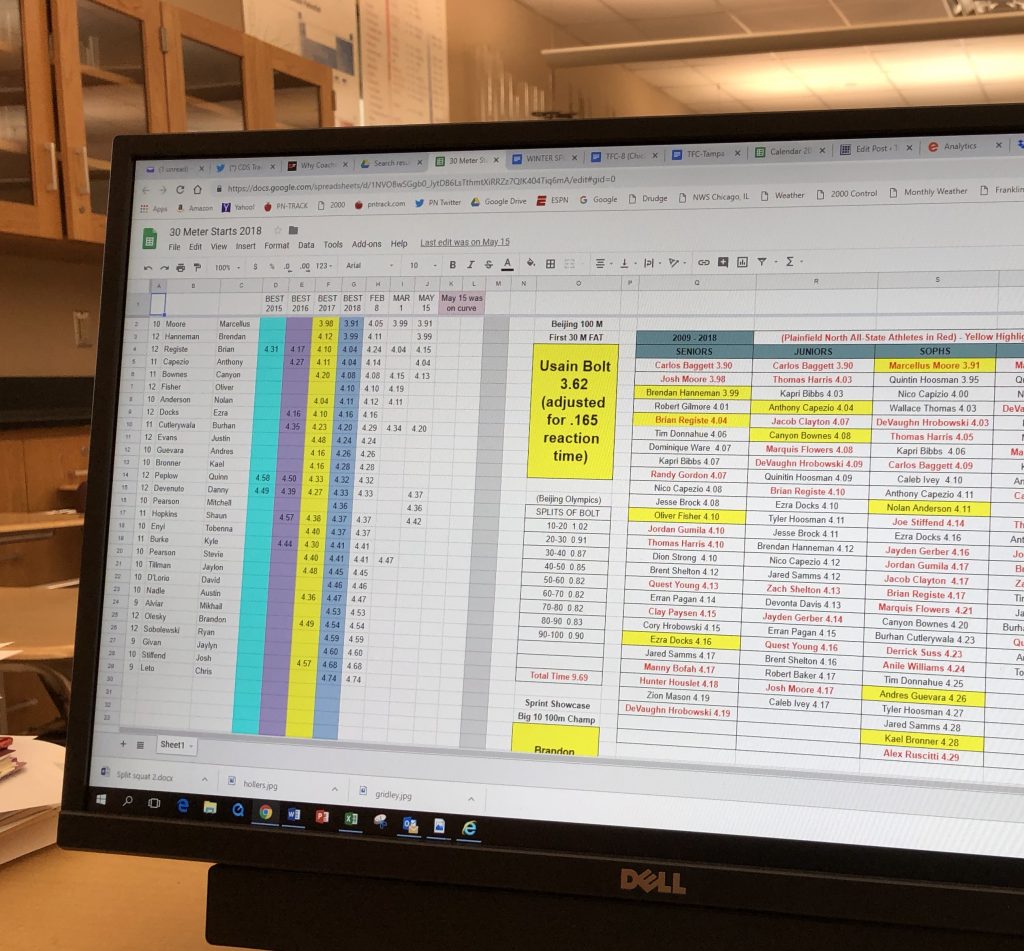

By 1999, I had graduated to a Macintosh computer and became a spreadsheet savant. Ranking athletes had entered the digital age. I posted those rankings on the bulletin board every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Every athlete checked the bulletin board at every session. I developed records by class AND by size of the athlete. Young skinny kids broke school records just as often as the hairy-legged, barrel-chested seniors.

I stayed 30 minutes after school and athletes had to pick one day a week to “stay late” or they would not get an “A” for Athletics. Remember, Athletics was a class. If there was an absence, make up was one additional “stay-late”.

The program ran itself. I walked around motivating kids and talking track. I kept an eye on proper form and would blow-up on anyone not lifting correctly. Anyone that didn’t want to be there got sent to the Kamikazes. The music was cranked to the max on a beat-up boom box. The atmosphere was amazing.

I hope you aren’t picturing one of those fancy suburban weight rooms. This was a pole barn about 50 steps from the end zone of the football field. The floor was concrete, the walls were plywood. The older equipment was covered with rust. None of that matters. Where there is a will, there’s a way.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, we did speed drills on the track. Every kid was taught to sprint at every session. Our speed drills included some plyometrics. I recorded, ranked, and published timed 40s. Winters were rather mild in Southern Illinois. Kids would often go shirtless despite 30-degree temperatures to achieve faster times. The only days we couldn’t sprint were days when there was ice or snow on the track. When that happened, we sprinted the permanent bleachers of the balcony of the beautiful Davenport Gym. We would sprint up, walk down, rest 20 seconds, then sprint again. We did two sets of seven. The basketball coach (Randy Smithpeters) would always throw a fit, even though the workout was taking place during 7th hour. The gym wasn’t truly his until after school. He eventually won and we were banned from the balcony.

Without access to the gym, we would test vertical and standing long jump outside of my Chemistry classroom. We recorded, ranked, and published everything.

Looking back, we were doing enough things right to really make a difference. The athletes bought in. Skinny guys got stronger. Slow guys got faster. We lifted heavily and sprinted maximally, but dosage was minimal. We never let today ruin tomorrow. We accepted small gains daily. We never did ANYTHING that resembled “getting in shape”. We were 100% alactic all winter. No track workouts.

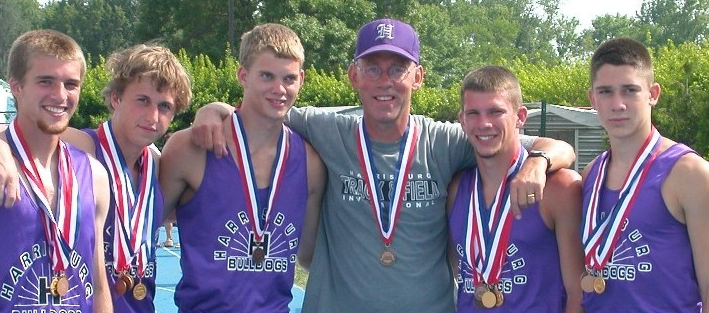

The picture above was taken after coaching my last race for Harrisburg High School, winning the IHSA Class A 4×4 in 2004. The week before, these guys shocked the world running 3:18.3. Four of them were products of my “Winter Work Group”, mixing BFS with FTC. The other was a wrestler.

I’d like to think of my winter work group years (1996-2004) as the golden age of Harrisburg sports.

♦ Football: 3A Runner Up 1997; 4A State Champions 2000

♦ Basketball: Class A Super Sectional 1997, 1998, 2001

♦ Track: Six Class A state trophies 1998, 1999, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004; two state championships

♦ Baseball: 239 wins, 67 losses; Class A Runner Up 2003, Class A State Champions 2004

I left Harrisburg in 2004 and never again worked in a weight room. At Franklin H.S. (TN), the weight room was the domain of the football team. My winter speed training group started with a handful of kids and eventually grew to around 50. We sprinted on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Our sprint sessions were so short, none of those kids missed their football weight lifting. Those doing a speed session simply started their lifting 45 minutes later than the rest. My speed training had the added benefit of relieving crowded conditions in the weight room.

I started at Plainfield North in 2006. We had so many kids (sometimes 150 would show up), we had to do two weight sessions and two speed sessions after school.

I’m proud of our work at Plainfield North but working with 150 kids is not optimum. Sometimes we waste too much time working with kids who have little, if any, chance of seeing quality time in football or on the track. There’s a reason why you can’t have fifty on a basketball team. You can’t effectively coach if there are too many kids and too many kids that will never play. I’ve had as many as fifty sprinters on my track team but I’ll never make that mistake again. 30-35 is the right number. However, when you are talking about off-season training, you can’t make it exclusive. We accept everyone. This is not football season or track season, this is the off-season. There are no footballs. There are no hurdles. We get stronger in the weight room, faster on the track. For more of how we do our winter program, check out Eight Weeks of Alactic Training.

Something New?

Last week I gave a private clinic presentation at Manitowoc High School in Wisconsin (my daughter was bummed I didn’t visit the Avery Salvage Yard a couple miles to the north). When talking about record-rank-publish, I mentioned BFS. It seemed like a couple of the coaches had not heard of Bigger, Faster, Stronger, so I explained what I liked about it. I explained how I liked the four-week cycle where records would be broken with regularity once you started the second cycle.

I kept thinking about BFS as I drove three hours home from Manitowoc. I’ve always believed in making the 40 the centerpiece for winter training because of its prominence in football. I wanted winter training to be just like training for a combine. That’s how I attracted football players to my track program. When football players loved winter training, they wanted to run track too. But, maybe I have enough football cred here at Plainfield North. Maybe it’s time to do something new on speed days.

I will always do speed drills. That’s how I coach sprinting. But, what about going to a cycle for speed days where kids could start breaking records like crazy?

The Speed Cycle

Maximum velocity speed training can be done two or three times per week. This year I’m starting a little earlier because our football team failed to make the playoffs due to a couple devastating injuries to key players. Our first speed training day will be Thursday, November 8. By starting a little earlier, it looks like we will get 21 speed days in before we start event-specific track practice. Remember, when feeding the cats, you build a sprint foundation, not an endurance foundation.

When we run sprints to be recorded, ranked, and published, each sprinter does a total of three. I would never say no to someone wanting to do a fourth, nor would I force anyone do three if they aren’t feeling up to it. Almost everyone does exactly three.

So, here’s the idea. Instead of timing a 40 with a secondary time of the final 10m of that 40 (two speed numbers in one sprint) every speed day all winter, I’m going to try something new. I am going to change the speed metric every day for a six workout cycle. Why? First of all, why not? Feed the Cats is a collection of ideas, philosophies, and opinions. Feed the Cats is not a recipe. The recipe can evolve as long as the pillars of the program remain.

The six workout cycle may keep our speed days fresher and more interesting. If you are sprinting two days a week, the cycle takes three weeks. If you are sprinting three days a week, the cycle takes only two weeks. I often tell coaches that our speed days are monotonous and repetitious. Why not change it up?

The most important reason for trying the speed cycle harkens back to what I learned from BFS twenty years ago. When athletes break records, the hit of dopamine is addicting. We want sprinters addicted to breaking records. In addition, high dopamine levels gives sprinters the ability to sprint faster. The six-workout cycle gives athletes a chance to set six benchmarks and then start breaking records.

Here’s the six workout cycle:

♦ 40 yard dash with the timing of a 10m fly at the end

♦ 15 yard acceleration into a 10 yard fly (blocks or 3-point stance) (cones at first two hurdle marks)

♦ 10 yard fly (full run-in, usually 25-30m)

♦ 20 yard competition flys (two guys racing through Freelap cones, full run-in)

♦ 40 yard dash with the timing of a 10m fly at the end – guantlet style

♦ 10m acceleration into a 20m relay zone (upright or 3-point start, like a relay)

You can keep track of our progress here: 2018-19 PN Speed Cycle (there are two tabs at the bottom)

Once you get through these six speed measurements, you start over and start breaking records like crazy. If you aren’t breaking records, you must not be getting enough sleep. Maybe you’re just going through the motions when doing speed drills. Maybe you’re weak and not getting stronger, or maybe you’ve been squatting too much. Maybe you need to eat nutritionally-dense foods instead of processed carbs. One thing’s for sure, getting faster is the expectation. Getting faster is the priority. Every athlete is expected to break speed records.

Breaking multiple records may be rocket fuel for cats.

Don’t forget the two big upcoming events. Please spread the word about TFC-Tampa to coaches living in Florida.

TFC-Chicago Dec 7-8

TFC-Tampa Dec 14-15

Tony Holler

@pntrack

When you retire from teaching this year, will you continue coaching? I hope so! Your a motivating, amazing, and knowledgeable coach!

Thank you. Yes, I plan on continuing to coach!

Coach Holler, as a strength coach reading your stuff has helped me evolve in many ways that have benefited the athletes I coach. My only regret is while I was in Naperville is that I didn’t make an effort to spend some time with you and pick your brain even more.

Thank you! Where are you now?

Do you always do yardage for Fly timing or do you also use Meters? Yards makes sense to equate to 40 times, but I feel like I usually see Track folks using meters.

We do 40y dash because football players want it. We measure other things in yards due to marks on the track. High hurdle marks are ten YARDS apart making it easy, no measuring required. IMO it doesn’t really matter, everything can be converted anyway. Thanks for reading!