The Difference Between the Countermovement and Squat Jump Performances Review

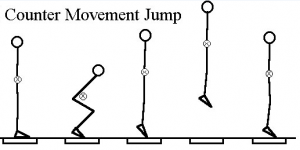

Thanks to the NFL Combine, the Vertical Jump, or the Counter Movement Jump for research purposes, has become an important to tool to differentiate players who exhibit power and those that don’t. Like the broad jump, teams like to see which athletes possess the power to move their center of mass either vertically or horizontally, possibly with the thought that this would indicate good first step quickness in or having an advantage to jump to a ball or make a tackle. But, fundamentally, it shows who has power.

In the last year, interesting research by Bas van Hooren has surfaced that looks at the difference between the countermovement jump (CMJ) and the Squat Jump (SJ) called

“The Difference between Countermovement and Squat Jump Performances: A Review of Underlying Mechanisms with Practical Applications”.

I like Van Hooren’s research. He always questions concepts what is normally held as the norm in Strength and Conditioning and looks for a better way to develop athletes so we can see a better transfer of training to work done off the field to on the field. In this case, he is looking at countermovement jump (CMJ) versus squat jump (SJ). The research begins with a review of previous explanations why there is a difference between the two jumps, which include residual force enhancements, stretch reflex, differences in kinematics, range of motion, storage and utilization of elastic energy and muscle slack, all of which he questions except for muscle slack.

Even though I really enjoyed his explanations, his “Implications for the Differences between Countermovement Jump and Squat Jump Performances” is when the research starts to become more useable for a coach. Van Hooren’s argument is that a better athlete should not have such a big difference between their CMJ and SJ. A big difference between CMJ and SJ, while having some good attributes of powerful movements, could be due to a “poor capability to reduce the degree of muscle slack and build up stimulation in the SJ.” Basically, muscle slack is the concept that a relaxed muscle hangs between two joints.

When an athlete goes to move, the joint angles change and the muscle becomes taut. Once the muscle has tension, it will contract. The whole process should take about 100 milliseconds. However, if the body is not used to dealing with slack or needs to move other joints to take up the slack, this contraction can take quite a bit longer. How this comes into play in the real world is that an athlete with the big difference between the jumps is the athlete who takes a longer period of time to gather to jump for a ball or explode in a direction.

I think this is also something that becomes apparent when you watch an experienced track athlete come out of the blocks in slow motion, where the movement is instant, compared to a novice who moves around quite a bit before they actually uncoil. This is also first step quickness, something every parent or coach claims their athlete’s lack. If I am going to step in a direction, it will be quicker if everything is tensed and ready to contract.

To improve athletic performance, it is suggested that you have to learn how to reduce muscle slack in order to become more explosive. One way to do this, is to create pretension using Co- contractions (Agonists and antagonists contract at same time to dampen signals from nervous system when high speed movements occur (which create noise). While dampening the neural firing, the contraction reduces muscle slack and make the movement more controlled and explosive in a safe manner).

This is the idea that by having a movement that forces other muscles to tighten, if the body will have more pretension and become more explosive. Some ways to accomplish this, is to apply unstable loads or unstable surfaces during training. This will ensure that there is not a lot of time to perform a large counter-movement and the only effective solution is to minimize slack to complete the movement especially when there is a time element involved. If the surface or load in unstable, the body will need to tighten to create stability so the athlete can perform his movement safely. If there is no time element involved it will allow the body to find another solution while not taking up the muscle slack.

Van Hooren throws a caution to training regarding weights. Once an external load is added to the exercise, the weight takes up slack. This could account for the fact that some athletes with big squat numbers don’t have big CMJ. He also cautions using single joint exercises and introduces previous research that compared single joint exercises to multi-jointed exercises and their impact on the vertical jump. As you can guess, the single joint group, while increasing their squat and had decrease in vertical jump.

Here’s some ideas on how I use this concept in my training. The train vertical jump, we do what we call ankle rocker jumps or slack jumps. you start by standing on a jump Matt, and we will have the minimal amount of Bend and hips slight Bend in the knees and a heavy Bend in the ankles with knees coming out or the toes. Who put her hands on her hips and go down into that quarter squat position, hold for two count and jump. you’re their learning to explode from a position that does not allow for much muscle Slack. I have found that the higher that athletes jump from this ankle rocker jump or slack jump the higher their vertical jump will become. More importantly, the more explosive they become on the field. Once we’ve trained this, and the squat jump gets closer to the counter-movement jump the more explosive the athlete becomes.

Another jump we will do, is to find a very low box anywhere from 6 to 12 inches and have the athlete from this ankle rocker position jump up onto the box and as soon as they land they’re going to explode up again and jump as high as possible. We have added time to the jump and with the short position the body doesn’t have time to create or deal with the slack. While we have the boxes out, we will also do a box jump from a very shallow angle as well.