Basketball Advice from a Sprint Coach

I’m known as a sprint coach but I spent the first half of my life focused on basketball. My father, Don Holler, coached 47 years at six high schools and one college (Aurora University). Dad, pictured above at Kiel Auditorium (Decatur vs. East St. Louis) almost 65 years ago, was a head coach in his first year out of college. My childhood was spent in school buses, locker rooms, and gymnasiums. Match-up zones and motion offense were discussed at the dinner table.

At age-23 I became the head basketball coach at the worst 2A school in Illinois (only two divisions in Illinois back in 1983). Harrisburg High School played in a conference with four schools twice their size. At six of the eight schools, the basketball coach was also the Athletic Director, meaning they hired the officials and handed them their checks, sometimes after the game. Four of those athletic directors were Hall of Fame basketball coaches (Rich Herrin, Lee Emory, Bob Bogle, and David Lee). In 1983, I inherited a 35 game losing streak and a near-impossible challenge.

My first five years were tough, showing progress but losing 92 games. Going into the 1987-88 season, Harrisburg had accomplished only one winning season in the previous 21 years, averaging 18 losses per season.

The 1987-88 season started well, winning eight of our first ten games with two close losses to state-ranked teams (Marion and Carbondale). We won the 16-team Eldorado Holiday Tournament, never trailing in any of our four games. Despite playing with a 6’1” center, we ran disciplined offense and destroyed teams that played us man-to-man. When teams went zone, we bombed threes. In the second half of the season, we went into a slump. Teams got tired of getting back-doored and back-picked for lay-ups and decided to make us win from the perimeter. My best two shooters picked the wrong time to go into prodigious slump. My team went on a miserable losing streak. We eventually got back on track but the damage had been done. We finished the year 13-12.

My teams went 14-11 and 13-13 in the next two years and I got fired in March of 1990. Lucky for me, I had been hired as head track coach the month before I was fired as basketball coach. In the next ten years, my track teams won three state championships.

I give you this historical perspective to let you know I’m not a total basketball outsider.

More important, I give you this historical perspective because of a mistake I made reacting to my team’s slump 30 years ago.

When things went south, I reacted like 99% of all coaches react to failure, I doubled down. Instead of giving my kids time off, I put them through “Hell Week”. We practiced before school, 6:15 until 7:45, and then practiced 2:30 until 5:00 after school. I was a monster. We did full-contact take-the-charge drills. We did loose-ball drills (one kid lost a tooth). We ran at the end of practice until someone puked. I was a product of World War II coaches, guys who had literally fought in WWII or were coached by guys who had fought. The answer to defeat was always hard work and toughness. Losing showed weak character and a lack of courage. The simple act of writing this paragraph has elevated my testosterone levels, which is not necessarily a good thing.

I’m a different type of coach now. I understand high performance and I’ve abandoned the military bullshit.

Back in August, I wrote New Ideas for Old School Football Coaches and two follow-up articles. The articles were well received and I know of several programs that changed what they do based on my ideas. I’ve received nothing but positive feedback.

I’ve done some consulting with basketball programs and recently a local basketball coach, Brett Hespel, asked for some basketball advice. Instead of writing Brett a three-hundred word email, I figured I’d write a three-thousand word blog.

Train like a Track Athlete

The hard-easy concept goes back to Bill Bowerman’s Oregon days (1948-1973). Bowerman realized that training was more effective when he allowed ample rest between hard workouts. The key word here is “hard”. Bowerman believed low-intensity training achieved nothing. World records are not the byproduct of moderate exercise. Bill Bowerman chose to train for high performance, not fitness. To achieve excellence in practice, Oregon never practiced hard two days in a row.

This is my take on hard-easy: “Sprint as fast as possible, as often as possible, staying as fresh as possible.”

Basketball coaches must decide, like Bowerman, what they want from practice. Should you try to “go hard” every day? Or, do you prioritize rest and recovery in an attempt to teach players to go faster and harder than they’ve ever gone? Would you rather have two practices per week in fifth gear or four practices in third gear? Most coaches demand consistent effort at every practice. They accept “the grind” of the season. Teams practice slow and hope to play fast in games. Believe it or not, many track coaches make the same mistake.

Here’s another one of my sayings: “Never let today’s workout ruin tomorrow’s workout if tomorrow’s workout is important.” I would rather practice less and feel great the next day than to practice until failure and trudge through the next day’s workout.

I can remember my dad telling his team 50 years ago, “We are going to work so hard in practice, games will feel easy.” This seemed to make sense to me at the time. Not anymore.

As a track coach, what if I adopted the “work hard in practice to make meets easy” philosophy? Would running ten 200s in practice make one 200 feel easy? Maybe. The problem comes with the unintended side effects of hard work. Athletes would RUN ten 200s, they would not SPRINT. It’s physically impossible to sprint 10 x 200. My guys would RUN each 200 in 25-28 seconds. How does this prepare someone to SPRINT a 21-second 200? How does slow in practice translate to fast in meets?

↑work + ↑volume = ↓intensity

There’s no arguing this fact. As a basketball coach, you have a choice. You can attempt to practice hard for two hours at every practice, or you can build your practice schedule to promote high-energy game-speed efforts.

When Dick Vitale talks about a formula for success, he refers to the three E’s, “Energy, Enthusiasm, and Excitement.” If these traits are important, coaches need to get away from the grind and put an emphasis on quality by incorporating rest and recovery.

Hormesis

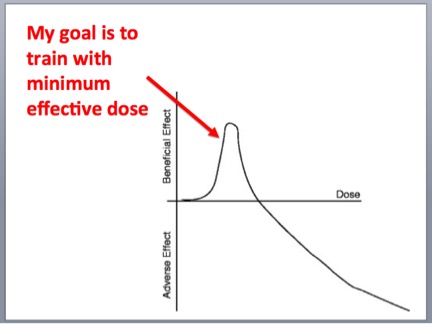

I talk about hormesis everywhere I go. I tell people about Paracelsus (1541), “Everything is a poison, nothing is a poison, it all depends on the dose.” I tell people about Hugo Schulz (1888), “Small doses stimulate, moderate doses inhibit, and large doses kill.” Hormesis is similar to The Law of Diminishing Returns. However, too much, too often, and too intense will do more than just diminish your returns.

Hormesis can be applied to food. Eating sustains life. Overeating is a national epidemic. Hormesis can be applied to medicine. Most medicines are poisonous in large doses. Alcohol is a perfect example of hormesis. The first couple drinks puts you in a good place. The third or fourth drink begins to inhibit. When you lose count, the alcohol starts to kill.

Obviously, the hormesis application for coaches is exercise. Training is like a poison. Training can stimulate, inhibit, or kill. Coaches are tough guys descended, in one way or another, from WWII survivors. Our natural instinct to celebrate hard work and beat our chests telling everyone how tough we are. But coaches are not leading a platoon against Rommel’s tanks. Coaches are directors of high performance. Coaches are in charge of skilled kids who compete against other skilled kids. We must keep our eye on the prize.

For more on hormesis, check out The Survival of King Mithridates.

Skill Work

Skills should be taught when the brain is alert and the body is rested. Tired and unfocused skill work borders on stupidity. In track, vaulters never practice tired. Jumpers only practice on days when they are fresh. Hurdlers go fast or go home (slow hurdling is beyond stupid).

Shooting is the most critical skill of basketball. I’ve witnessed basketball practices where teams did drills, scrimmaged, and then ran sprints until exhausted. The skill of shooting was NEVER addressed.

I’ve watched middle school teams spend more time on out-of-bounds plays than on shooting the ball correctly.

Bobby Knight believed “how to play” was infinitely more important than “plays”.

Ball-handing is another skill that can be practiced and improved. In my opinion, scrimmage situations and AAU games do not improve ball-handling. If you think about it, only one player has the ball in any live basketball situation. Two teams, one ball.

John Wooden said “Never mistake activity for achievement.” Too many basketball coaches are proud of their busy practices. Just because players are on the move doesn’t mean jack shit. There can be tons of activity in a practice while shooting, passing, and ball-handling skills remain unchanged.

John Wooden reminded coaches what it takes to improve fundamentals. Here are Wooden’s “Eight Laws of Learning”:

#1 Explanation

#2 Demonstration

#3 Imitation

#4 Repetition

#5 Repetition

#6 Repetition

#7 Repetition

#8 Repetition

Cherish Reps

This phrase comes from my son, Alec. Alec Holler coached the best hurdler in Illinois history. Travis Anderson set the state record in the 110 Highs in 2016 running 13.59. Last year, Travis Anderson won both the 110 highs and 300 intermediates leading his team to the IHSA State Championship. Travis was trained with a less-is-more, minimum-effective-dose program (we call it “Feed the Cats”). Not once did Travis go over more than the first two hurdles in practice. Every workout was done in spikes at full speed. Every rep was timed. Every rep was CHERISHED.

“Feed the Cats” is counter-intuitive to coaches of team sports. Every practice features hundreds of half-assed reps with coaches yelling for more intensity and more focus. If coaches can’t get their players to play hard, they run sprints. Volume is cherished.

When Alec sees team sports being coached without cherishing reps, Alec sees dysfunction. How can you play games at a high intensity and extreme focus if practice is half-speed?

Record, Rank, and Publish

I should have trademarked “Record, Rank, and Publish”. I became a spreadsheet geek before most people knew what a spreadsheet was. Remember AppleWorks and ClarisWorks?

As a track coach, I found that recording times, ranking athletes, and then posting their results created meaning and significance. Because I time sprints in practice (Freelap timing system), kids never forget their spikes.

My record, rank, and publish idea came from my dad. As a basketball coach, dad would always “chart free throws”. Rankings were then posted on a bulletin board. Why? Because when you post the number of free throws made out of 50 attempts, players cared. It’s that simple.

As a basketball coach, I expanded this idea to include more than just free throws. I charted 50 three-pointers at least twice a week. For those of you wanting to know how we did this, here goes.

Two guys would pair up. The first guy would shoot a set of ten going from one wing to the other. The rebounder would wait until the shooter’s feet were set before delivering the ball (I’m a big believer in stepping into the 3). When the set of ten was completed, the rebounder would become the shooter and shoot ten. After five sets of ten each, both players would report their total to the coach.

The other version was more of an “around the world” format. The shooter would start at the wing, advance to the top of the key, to the other wing, to the corner, back to the wing, back to the top of the key, back to the wing he started at, to the corner, back the to the original wing, then to the other wing. The set of ten included three shots from both wings, two from the top, and one from each corner (corner threes are poor percentage shots). Once again, both shooters would report the total of their five sets of ten.

Of course we shot 50 free throws as well. I learned at an early age, in over 80% of all basketball games, the team that makes the most free throws wins the game. This taught me three things: 1) don’t foul, 2) attack the basket to draw fouls, 3) make free throws.

Once my team was struggling from the line and I asked my Athletic Director if he had any tips for me. Gene Haile had coached Jerry Sloan at McLeansboro (1956-1960), so he knew a thing or two about basketball. Gene suggested 50 free throws before school and another 50 during practice. My team got better quick.

I also recorded a set of 50 interior shots. One set of 10 was from the mid-post pivoting towards the baseline and shooting a bank shot. UCLA dominated college basketball during my youth and seemed to use the glass on every possible shot. The next set was shot from the other mid-post, again bank shots. Set three was mid-post turning into the lane shooting a hook or fade. Set four went to the other mid-post, again hook or fade. Set five was done from mid-lane and involved alternating left and right pivots using a step-through to score (think Hakeem Olajuwon). The drill was done in pairs, alternating sets. When both players completed their five sets, they reported their number made.

Many college coaches have the manpower to record everything that happens in practice. Every rebound and assist is recorded. Every player who goes to the floor after a loose ball is noted. Every deflection. Every make. Every miss. Record, Rank, and Publish.

Develop More Than a Starting Five

Every basketball coach says he loves all his players equally but few practice what they preach. On the typical basketball team, half the players are important and the other half are forgotten. The guys on the bench might as well not attend games. They gain nothing from the process of watching the game played by those who get to play.

My track team times more sprints in practice than any team I know. We time flys of 10, 20, 30, and 40 yards. We also time metric distances, 10, 20, and 35 meters. We time the 40-yard dash and 30-meter block start. We time four different lactate workouts. Everything we time is recorded, ranked, and published on a Google Sheet and tweeted out for hundreds of people to see. By doing this, I give my young kids and slower athletes a chance to see improvement which may motivate them to keep training with intensity.

I would encourage basketball coaches incorporate scrimmages for their non-starters. On recovery days (and you should have a recovery day before and after every hard practice), conduct a fully officiated game with the kids who sit the bench. Think about the life of a bench-warmer; they practice four days a week and sit three. Their parents come to games to watch them sit. These kids typically regress during the season.

Make sure you don’t promote these in-practice games as “scrub games” or “B-team scrimmages”. Make them a big deal. If you have enough kids, play four quarters on the clock. If you don’t want to mess with the clock, play four quarters, first team to score 20 ends the quarter. Shoot free throws. Officiate. Have your starters keep the scorebook and detailed stats. Video the scrimmages (even if you don’t watch the video!). Post the stats and keep a running total for the year. Allow those kids to see improvement and give them something to look forward to. If you ever had a son who didn’t get to play much, you’d understand.

If you don’t have ten players, play four on four half-court. Play four quarters, each to 16 points. Shoot free throws. Even if you have only six players, play three on three, each quarter to 12 points. Whatever the format, keep stats. Record, Rank, and Publish. Don’t be afraid to tweet about it. Imagine an entire team of motivated kids getting better week by week.

Encourage a Second Sport

During my coaching career, I’ve witnessed the evolution of basketball. I began my career playing and coaching the game of basketball when dunks were technical fouls and perimeter shots were only worth two points. Believe it or not, basketball, in many ways, was a better game back then.

Basketball players have changed as well. In the 1970s, basketball players (the world’s best athletes), usually played multiple sports. Basketball was a two-season sport. If you played basketball in the winter, you played in the summer. Much of summer ball was three-on-three, make-it-take-it. The winning team stayed on the court. Much of summer basketball was played in the evening on outdoor courts. Most schools opened their gym in the summer to give players a place to play.

Today, in some places, AAU has superseded high school programs. Many AAU coaches get wealthy brokering back-door deals with shoe companies and unethical college programs. The modern-day high school basketball coach is sometimes ignored in the recruitment process.

Camron Donatlan of Aurora West was a basketball player until he tried high jumping as a sophomore. Donatlan won the IHSA state championship in both his sophomore and junior seasons. The picture above shows a solid attempt at 7’3″. Cameron will attempt the 3-peat this spring.

AAU creates specialized athletes who play basketball year-round. Instead of improving athleticism and educational opportunities, AAU basketball players travel the country dribbling and shooting layups twelve months a year.

If kids only play basketball, they never sprint. It takes at least 25-30 meters to accelerate to top speed (more with elite sprinters). High school basketball courts are 25.6 meters long. College courts are 28.6 meters long. No one gets to top speed, ever. Misguided coaches believe sprinting is irrelevant to basketball.

If you have economy car and sports car, both can travel at 70 mph. However, the sports car can go 70 easier than the economy car. The fact that a sports car can reach speeds of 150 mph makes 70 mph feel comfortable. Too many basketball players are like an economy car, they’ve never developed their top speed.

I love this statement made by Josh Bonhotal, S&C coach for Purdue Basketball:

“Too often, I see coaches overemphasizing conditioning during the off-season and never developing absolute capacities of strength, power, and speed. In particular, a common mistake is to attack repeat sprint ability when you have never truly developed speed and thus sprint ability itself.”

Max speed sprinting is, in my opinion, the Holy Grail of athleticism. The ability to sprint at 10 m/sec is the ultimate fast-twitch exercise. Nothing unassisted is faster. Sprinting potentiates jumping and agility. I believe sprinting changes the nervous system and changes athleticism.

Music has been a part of formal education for hundreds of years. Playing the piano or violin makes people smarter. Sprinting is to the athlete what music is to the brain.

If sprinting is the Mecca of athleticism, why not encourage track in the spring?

Athletics were meant to be a part of a balanced education. Let’s get back to the way it should be.

+++

Tony Holler has taught Chemistry and coached track for 36 years at three different high schools, Harrisburg (IL), Franklin (TN), and Plainfield North (IL). Inducted into the ITCCCA Hall of Fame in 2015, Holler’s teams have continued to feature great sprinters. Along with Chris Korfist, Holler co-directs the Track Football Consortium held twice a year (June and December). Holler has written over 100 articles promoting the sport of track and field and sharing everything he knows. His articles can be found at ITCCCA.com, FreelapUSA.com, and SimpliFaster.com. You can follow Coach Holler on Twitter @pntrack and email him at tony.holler@yahoo.com.

Don’t miss videos from past consortiums! Videos

An old friend of mine, Rus Bradburd, commented on this article through email:

.

“I recall Haskins practices being 45 minutes near season’s end…the players wanting to stay, him kicking them out. And Lou’s idea: running sprints had to be full court, no “ladders/suicides” which wore down the legs more than a straight sprint. Down and back twice, that was Lou. And we’d do a few of them. (Haskins rarely had them run sprints…thought they wouldn’t practice hard if they knew sprints were waiting at the end.)….”

.

Rus is referring to Hall of Famers Don Haskins of UTEP and Lou Henson of New Mexico (formerly Illinois). Rus was assistant coach at both schools. I love the anecdotes from both UTEP and New Mexico State. Two coaches who “get it”.

.

Rus Bradburd is the author of two of the best basketball books ever written, “Paddy on the Hardwood” and “Forty Minutes of Hell”. Rus is presently working on “All the Dreams We’ve Dreamed: A Story of Hoops and Handguns on Chicago’s West Side”.

.

Some of you may remember Rus Bradburd as the greatest dribbler in the history of the world.