Overlooked Connections between Team Sports and Track and Field – Part 1

By Rob Assise, Homewood-Flossmoor High School

Track programs should strive to create an all-star team of their school’s athletes. Coaches should target the best football, soccer, basketball, cross country, wrestlers, P.E. class superstars, or anyone else with athletic ability. The primary selling point for running track and field is improving speed, and there is no better place for a high school athlete to improve this quality than in a track program which builds its training around enhancing maximum velocity.

Improving top-end speed has a global impact on overall athleticism. Athletes who get faster:

- Absorb and produce greater forces in less time (often through improvements in strength and technique).

- Improve total body coordination. Small changes in technique can often lead to huge improvements, but making those changes is a substantial challenge to an athlete’s coordination.

- Develop a greater speed reserve, which leads to improved repeat sprint ability (essential for success in team sports).

- Improve their ability to accelerate (a pre-requisite for maximum velocity).

Nothing can mimic what an athlete experiences when sprinting maximally. The neurological demand due to the speed and forces produced make sprinting the king of all exercises. Athletes who choose to participate in track and field are exposed to sprinting on some level. It will be addressed most often for sprinters, jumpers, and hurdlers, but is also a component of the training of distance runners and throwers. With this being said, the benefits of participating in track and field do not stop at just improving maximum speed. This article will address overlooked benefits in the sprint hurdles, triple jump, as well as the 4×100 and 4×400 m relays.

100/110 m High Hurdles

The athleticism it takes to be a quality hurdler is vastly underappreciated. Watching a clean hurdle race is a beautiful symphony. Numerous components of athleticism come together to create a mesmerizing event. The ability to coordinate clearing 10 barriers by an inch or two in varying conditions (temperature, wind, competition) requires extreme precision. Being precise in an unstable environment is a critical skill in team sports. For example, wide receivers often make slight alterations to a route based on what they see or feel.

Speed, coordination, and mobility are obvious characteristics a hurdler must possess to be successful. Another important skill which connects well with team sports is vision. According to strength and conditioning specialist Derek Hansen,

“Their (a hurdler’s) vision is not focused on individual hurdles, but an array of barriers. Focusing too much on one particular barrier can result in disaster as attack angle, rhythm and flight mechanics can be disrupted. Good vision is not about locking onto one specific hurdle, but scanning through the rows and not panicking about any one in particular. While you are focusing on what you need to do, barriers are crashing around you and limbs are flying into your lane.” [1]

Team sport athletes have similar demands in regards to vision. In basketball and soccer, players who can see the whole picture have an advantage when it comes to passing, defending, and making appropriate cuts/runs off of the ball. In football, a quarterback is required to see the whole field during a pass, a running back’s peripheral vision can allow him to exploit an opening, and a defensive back playing zone often has to read and react to the actions of multiple receivers.

Video 1: IHSA 110 m High Hurdles state meet record holder Travis Anderson showcasing phenomenal athleticism by maintaining his composure even with a glitch in rhythm. Anderson was one of Edwardsville’s top skill players in football, but his junior and senior seasons were limited due to a broken collarbone.

Triple Jump

If you want to see a remarkable display of speed, strength, power, and coordination click here to view a slow motion version of the 2012 London Olympic Men’s Triple Jump Final. Elite triple jumpers exert a force of 22 TIMES their body weight during the contact between the hop and step phase. [2] For a 200 pound triple jumper, that is 4400 pounds! On one leg. For around 15 tenths of a second. An additional study of jumpers (who have marks equivalent to elite high schoolers) showed forces of 15.2 times their body weight. [3] I am an advocate of the weight room, but I have yet to find anything that can compete with these forces. The most demanding portion is the initial contact where the force is being absorbed. The ability to absorb force and quickly transition to producing force is critical for team sport athletes when they are required to change direction. The image below summarizes this concept.

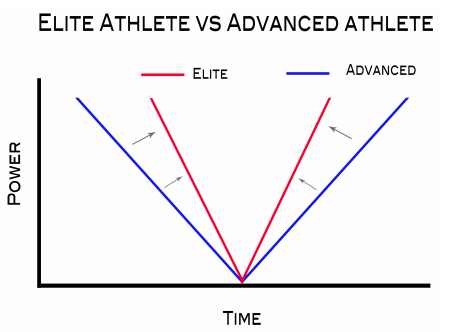

Image 1: This graph was taken from Cal Dietz and Ben Peterson’s “Triphasic Training.” (p. 73) The descending portion of the graph shows the athlete’s ability to absorb force and the ascending portion shows force production. The athlete who is able to absorb and produce more force in less time (red) will be more explosive than an athlete who can produce the same amount of force in a longer time (blue). Any training should focus on narrowing the V!

Image 1: This graph was taken from Cal Dietz and Ben Peterson’s “Triphasic Training.” (p. 73) The descending portion of the graph shows the athlete’s ability to absorb force and the ascending portion shows force production. The athlete who is able to absorb and produce more force in less time (red) will be more explosive than an athlete who can produce the same amount of force in a longer time (blue). Any training should focus on narrowing the V!

Triple jumpers consistently practice the ability to exert more force in less time in their specific training. Besides sprinting to enhance max velocity, the various bounding complexes performed can take an already explosive athlete to another level.

Video 2: IHSA Triple Jump state meet record holder Cameron Ruiz exhibits an incredible ability to absorb and produce force. The underlying component of this ability is tremendous coordination, which allows him to maximize the free energy produced by the stretch reflex. Ruiz is currently a defensive back at Northwestern University.

The 4×100 and 4×400 Meter Relays

I often say that the 4×400 meter relay is the most exciting event in track and field and the 4×100 meter relay is the most intense. On top of being the last event of the meet, the 4×4 allows for numerous lead changes and gap closings. It is always fun to watch an elite sprinter get the baton with a 20 meter deficit and see what strategy will be used to close the gap.

The 4×1 does not involve much strategy once the gun goes off. It is all about pure speed! This video from BBC Live 5 Sport does a superb job of explaining just how difficult executing a smooth 4×1 can be. It is a reasonable expectation for the baton to make its way around the track legally, but the skill which is involved in doing so is not appreciated as much as it should be.

The majority of track and field is an individual sport with a team component. The relays are the exception to this because they are a team event with an individual component. This makes them more similar to team sports. While every track and field athlete wants to perform well in their individual events for their team (and themselves), the degree to which an athlete wants to perform well for their relay is even more significant. Every year I see athletes have substantial breakthroughs in relays and are then able to carry it over to an individual event. It seems to work the other way around less often. Relays give track athletes a more direct opportunity to be accountable for something bigger than themselves (I feel track and field as a whole does this, but there is just something unique about being part of a relay). Team sport coaches would agree that when athletes make a commitment to each other, special things happen.

Video 3: Marcell Ellis does a great job of keeping his composure taking a handoff in traffic and then reeling in the competitors in front of him. Marcell is undecided, but will play football (and most likely run track) at the collegiate level next fall.

Video 4: Here Marcell is in even a more pressure-packed situation (knowing he will receive the baton in first in the Illinois State Final). Football players often make ideal relay runners because of their experience dealing with stressful situations under the Friday night lights.

Part 2 of this series will focus on the jumps, throws, and some general considerations.

+++

Rob Assise is in his 15th year teaching mathematics and coaching track and field at Homewood-Flossmoor High School. He also has experience coaching football and cross country. Rob has attended all six Track-Football Consortiums and was a presenter at TFC-6. Additional writing of his can be found at Simplifaster, Just Fly Sports, and ITCCCA. He can be reached via e-mail at robertassise@gmail.com or Twitter @HFJumps.

References

[1] Hansen, Derek M. “Why Do Hurdlers Make Great Football Players?” Strength Power Speed. December 18, 2011. http://www.strengthpowerspeed.com/why-do-hurdlers-make-great-football-players/

[2] Robichon, Franck. “Faster, Higher, Stronger: Science Shows Why Triple Jumpers may be the Ultimate Olympians.” The Conversation. August 16, 2016. https://theconversation.com/faster-higher-stronger-science-shows-why-triple-jumpers-may-be-the-ultimate-olympians-63975

[3] Perttunen JO, Kyröläinen H, Komi PV, Heinonen A. “Biomechanical Loading in the Triple Jump.” Journal of Sports Science. May, 2000;18(5):363-70.